| ||||

Part I: Address to the United Nations

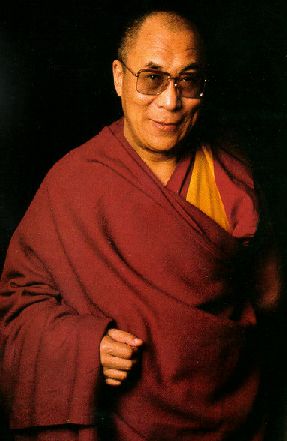

Excerpts from the Dalai Lama's Address.

No matter what country or continent we come from we are all basically the same human beings. We have the same common human needs and concerns. We all seek happiness and try to avoid suffering regardless of our race, religion, sex or political status.

have the right to pursue happiness and live in peace and in freedom.

As free human beings we can use our unique intelligence to try to understand ourselves and our world. It is very often the most gifted, dedicated and creative members of our society who become victims of human rights abuses. Thus the political, social, cultural and economic developments of a society are obstructed by the violations of human rights. Therefore, the protection of these rights and freedoms are of immense importance both for the individuals affected and for the development of the society as a whole.

Some people think that causing pain to others may lead to their own happiness or that their own happiness is of such importance that the pain of others is of no significance. But this is clearly shortsighted. No one truly benefits from causing harm to another being. Whatever immediate advantage is gained at the expense of someone else is short-lived. In the long run causing others misery and infringing upon their peace and happiness creates anxiety, fear and suspicion for oneself.

The key to creating a better and more peaceful world is the development of love and compassion for others. This naturally means we must develop concern for our brothers and sisters who are less fortunate than we are.

We need to think in global terms because the effects of one nation's actions are felt far beyond its borders. Respect for fundamental human rights should not remain an ideal to be achieved but a requisite foundation for every human society.

| we should also be aware of our responsibilities. If we accept that others have an equal right to peace and happiness as ourselves do we not have a responsibility to help those in need? |

All human beings, whatever their cultural or historical background, suffer when they are intimidated, imprisoned or tortured. We must insist on a global consensus not only on the need to respect human rights world wide but more importantly on the definition of these rights.

Some Asian governments have contended that the standards of human rights laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are those advocated by the West and cannot be applied to Asia and others parts of the Third World because of differences in culture and differences in social and economic development. I do not share this view and I am convinced that the majority of Asian people do not support this view either, for it is the inherent nature of all human beings to yearn for freedom, equality and dignity, and they have an equal right to achieve that. I do not see any contradiction between the need for economic development and the need for respect of human rights.

The rich diversity of cultures and religions should help to strengthen the fundamental human rights in all communities, because underlying this diversity are fundamental principles that bind us all as members of the same human family. Diversity and traditions can never justify the violations of human rights. Thus discrimination of persons from a different race, of women, and of weaker sections of society may be traditional in some regions, but if they are inconsistent with universally recognized human rights, these forms of behavior must change. The universal principles of equality of all human beings must take precedence.

It is mainly the authoritarian and totalitarian regimes who are opposed to the universality of human rights. It would be absolutely wrong to concede to this view. On the contrary, such regimes must be made to respect and conform to the universally accepted principles in the larger and long term interests of their own peoples. The dramatic changes in the past few years clearly indicate that the triumph of human rights is inevitable.

There is a growing awareness of peoples' responsibilities to each other and to the planet we share. This is encouraging even though so much suffering continues to be inflicted based on chauvinism, race, religion, ideology and history. A new hope is emerging for the downtrodden, and people everywhere are displaying a willingness to champion and defend the rights and freedoms of their fellow human beings.

Brute force, no matter how strongly applied, can never subdue the basic human desire for freedom and dignity. It is not enough, as communist systems have assumed, merely to provide people with food, shelter and clothing. The deeper human nature needs to breathe the precious air of liberty.

| |

There still remains a major gulf at the heart of the human family. By this I am referring to the North-South divide. Today's economic disparity can no longer be ignored. It is not enough to merely state that all human beings must enjoy equal dignity. This must be translated into action. We have a responsibility to find ways to achieve a more equitable distribution of the world's resources.

We are witnessing a tremendous popular movement for the advancement of human rights and democratic freedom in the world. This movement must become an even more powerful moral force, so that even the most obstructive governments and armies are incapable of suppressing it.

Human rights, environmental protection and great social and economic equality, are all interrelated. I believe that to meet the challenges of our times, human beings will have to develop a greater sense of universal responsibility. Each of us must learn to work not just for one self, one's own family or one's nation, but for the benefit of all humankind. Universal responsibility is the best foundation for world peace.

| |

Part II

Images of the Dalai Lama's Tibet

Crossing over into Tibet, the gates of heaven were opened and a mysterious world of luminous colors stretched out before one's eyes. |

| "I was born on July 6, 1935 in the far northeastern province of Amdo in the village of Taktser, a small and poor settlement which stood on a hill overlooking a broad valley. My parents were small farmers among about 20 other families making a precarious living off the land raising barley, buckwheat, and potatoes. When I was not quite three years old, a search party had been sent out to find the new incarnation of the Dalai Lama." While laying in state after death, the head of the previous 13th Dalai Lama had turned to face the Northeast - the province of Amdo - thus indicating the region where he would take rebirth. Shortly after that one of the senior lamas had a vision of a house with strangely shaped guttering. After finding the house, various relics of the previous Dalai Lama along with toys attractive to a small boy were presented to the three year old Lhamo Thondup (the child Dalai Lama's original given name). The child recognized the head of the search party, calling out to him, and also correctly identified only those items that were his in his former life, saying 'It's mine, It's mine.' The Fourteenth Dalai Lama had been found. Excerpted from: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama |

| Journey to Lhasa "We now entered some of the most remote and beautiful countryside in the world: gargantuan mountains flanked by immense flat plains which we struggled over like insects. Occasionally, we came upon the icy rush of meltwater streams that we splashed noisily across. And ever few days we would come to a tiny settlement huddled amongst a blaze of green pasture, or clinging as if by its fingers to a hillside. Sometimes we could see in the far distance a monastery perched impossibly on top of a cliff. The journey took three months. I remember very little detail apart from a great sense of wonder at everything I saw: the fast herds of wild yaks ranging across the plains, the smaller groups of wild asses and occasionally a shimmer of gowa and nawa, small deer which were so light and fast they might have been ghosts. I also loved the huge flocks of hooting geese we saw from time to time." From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama |

| "My mother was undoubtedly one of the kindest people I have ever known. She was truly wonderful and loved, I am quite certain, by all who knew her. She was very compassionate. Once, I remember being told, there was a terrible famine in nearby China. As a result, many poor Chinese people were driven over the border in search of food. One day, a couple appeared at our door, carrying in their arms a dead child. They begged my mother for food, which she readily gave them. Then she pointed to the child and asked whether they wanted help to bury it. When they had caught her meaning, they shook their heads and made it clear that they intended to eat it. My mother was horrified and at once invited them in and emptied the entire contents of the larder before regretfully sending them on their way. Even if it meant giving away the family's own food so that we ourselves went hungry, she never let any beggars go empty-handed." From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama |  |

"Although it is very beautiful, the Potala was not a place to live. It was built on a rocky outcrop known as the 'Red Hill' on the site of a smaller building, at the end of the time of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, who ruled during the seventeenth century. When he died in 1682, it was still far from completion so his faithful Prime Minister concealed the fact of his death for fifteen years until it was finished, saying only that His Holiness had embarked on a long retreat. As a child, I was given the Great Fifth's own bedroom on the seventh (top) story. It was pitifully cold and ill-lit. One of the compensations of living in the Potala was it contained numerous storerooms. These were far more interesting to a small boy than those rooms which contain silver or gold or priceless religious artifacts. I much preferred the armoury with its collection of old swords, flintlock guns and suits of armor. But even this was as nothing compared with the unimaginable treasure in the rooms containing some of my predecessor's belongings. Amongst these I found an old air rifle, complete with targets and ammunition, a telescope, and piles of illustrated books in English about the First World War." From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama |

| "There were about ten Europeans living in Lhasa throughout my childhood. I did not see much of them and it was not until Lobsang Samten brought Heinrich Harrer to me that I had a chance to get to know an inji as Westerners were known in Tibet. Heinrich Harrer turned out to be a delightful person with blond hair such as I had never seen before. I nicknamed him Gopse, meaning 'yellow head'. As an Austrian, he had been interned during the Second World War, a prisoner of the British in India. But somehow he had managed to escape with a fellow prisoner named Peter Aufschnaiter. Together they made their way to Lhasa. This was a great achievement, as Tibet was officially out of bounds to all foreigners. It took them about five years living as nomads before they finally reached the capital. When they arrived, people were so impressed with their bravery and persistence that the Government permitted them to stay. Naturally, I was one of the first to hear of their arrival and I became quite curious to see what they were like, especially Harrer, as he quickly developed a reputation as an interesting and sociable person. He spoke excellent colloquial Tibetan and had a wonderful sense of humour, although he was also full of respect and courtesy. As I began to get to know him better, he dropped the formality and became very forthright, except when my officials were present. I greatly valued this quality." From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama |  Heinrich Harrer, Austrian Adventurer, Mountain Climber |

| Heinrich Harrer's Account: "The fifteenth of each Tibetan month is one of the great days. There is a magnificent precession in which the Dalai Lama takes part. Tsarong had promised as a window in one of his homes overlooking the Parkhor. While the brightly colored crowd flowed through the streets we sat at our window with Mrs Tsarong. Our hostess was a friendly old lady who had always mothered us. Night fell swiftly, but soon the scene was brightly illuminated with a swarm of lights. There were thousands of flickering butter lamps. The moon came up over the roofs to throw more light on the proceedings. The months are lunar in Tibet so it was full moon on the fifteenth. Everything was ready: the stage was set and the great festival could now begin. The voices of the crowd were hushed in anticipation. The great moment had come. The cathedral doors opened and the young God-King stepped slowly out, supported on the right and left by two abbots. The people bowed in awe. According to strict ceremonial they should prostrate themselves but today there was no room. As he approached they bowed, as a field of corn bends before the wind. No one dared to look up. With measured steps the Dalai Lama began his solemn circuit of the Parkhor. From time to time he stopped before the figures of butter and gazed at them. He was followed by a brilliant retinue of all the high dignitaries and nobles. After them followed the officials in order of precedence. In the procession we recognized our friend Tsarong, who followed close behind the Dalai Lama. Like all the nobles, he carried in his hands a smoldering stick of incense. The awed crowd kept silent. Only the music of the monks could be heard - the oboes, tubas, kettledrums, and chinels. It was like a vision of another world, a strangely unreal happening. In the yellow light of the flickering lamps the great figures of molded butter seemed to come to life. We fancied we saw strange flowers tossing their heads in the breeze and heard the rustling of the robes of gods. The faces of these portentous figures were distorted in a demonic grimace. Then the God raised his hand in blessing. Now the Living Buddha was approaching. He passed quite close to our window. The woman stiffened in a deep obeisance and hardly dared to breathe. The crowd was frozen. Deeply moved we hid ourselves behind the women as if to protect ourselves from being drawn into the magic circle of this Power. We kept saying to ourselves, 'It is only a child.' A child indeed, but the heart of the concentrated faith of thousands, the essence of their prayers, longings, hopes. Whether it is Lhasa or Rome - all are united by one wish: to find God and to serve Him. I closed my eyes and hearkened to the murmering prayers and the solemn music and sweet incense rising to the evening sky." From: Seven Years in Tibet, by Heinrich Harrer |    |

Dark Times for Tibet

Chinese Military Trucks parked under the Holy Potala

"Already the previous autumn there had been cross-border incursions by Chinese Communists, who stated their intention of liberating Tibet from the hands of imperialist aggressors - whatever that might mean.

Two months later in October (1950), our worst fears were fulfilled. News reached Lhasa that an army of 80,000 soldiers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army had crossed the Drichu river east of Chamdo (there were less than 8500 men in the Tibetan army). Reports on Chinese Radio announced that, on the anniversary of the Communists coming to power in China, the 'peaceful liberation' of Tibet had begun."

From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama

|

Flight Into Exile

"At a few minutes before ten o'clock, now wearing unfamiliar trousers and a long black coat, I stepped outside. I could sense the presence of a great mass of humanity as I stumbled along (in the dense Tibetan darkness), but they did not take any notices of us and, after a few minutes walk, we were once more alone. We had successfully negotiated our way through the crowd, but now there were the Chinese to deal with. The thought of being captured terrified me. For the first time in my life I was truly afraid - not so much for myself but for the millions of people who put their faith in me. If I was caught all would be lost. Our first obstacle was the tributary of the Kyichu river that I used to visit as a small child. To cross it we had to use stepping stones, which I found extremely difficult to negotiate without my glasses. More than once I almost lost my balance. We then made our way to the Kyichu itself where a small party of ferrymen were waiting for us. The crossing went smoothly, although I was certain that every splash of the oars would draw down machine gun fire on us. There were many tens of thousands of People's Liberation Army stationed in and around Lhasa at that time and it was inconceivable that they would not have patrols out. On the other side, we met up with a party of freedom fighters who were waiting with some ponies. As soon as the others arrived, we set off towards the hill and the mountain pass, called Che-La that separates the Lhasa valley from the Tsangpo valley. At the top of the 16,000 foot pass, the groom who was leading my pony stopped and turned it round, telling me that this was the last opportunity on the journey for a look at Lhasa. The ancient city looked serene as ever as it lay spread out far below. I prayed for a few minutes before dismounting and running on foot down the sandy slopes. We then rested again for a short while before pushing on towards the banks of the Tsangpo.

On about the fifth day, we were overtaken by a posse of horsemen who brought terrible news. Just over forty-eight hours after my departure, the Chinese had begun to shell the Norbulingka and to machine-gun the defenceless crowd, which was still in place. My worst fears had come true. I realised that it would be impossible to negotiate with people who behaved in this cruel and criminal fashion."

From: Freedom in Exile, the Autobiography of the Dalai Lama

After three weeks of exhausting travel in the worst of weather, the Dalai Lama and his party reached the freedom of India where he established the Tibetan Government in Exile at Dharamsala.

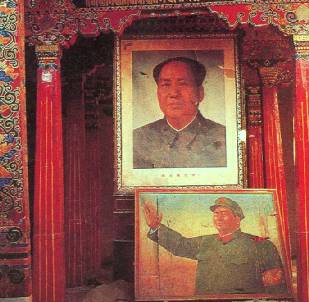

Impact of the Chinese Occupation

Approximately 1.2 million Tibetans died during the thirty years following the Chinese occupation in 1949. About 125,000 Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama into exile, to settle in India or other parts of the world. Due to population transfers of Chinese to Tibet and forced birth control of Tibetans still in Tibet, the Chinese in Tibet now outnumber native Tibetans. Almost all the monasteries in the country were systematically destroyed by the officially atheist Chinese Government and the practice of Tibetan religion (their primary way of life before the occupation) was strictly outlawed. It was especially forbidden to even possess a picture of the Dalai Lama. Policies to stamp out Tibetan culture are in effect even today. An official Chinese Government document from 1991 says: "We should oppose all those who work to split the motherland. There should be no hesitation in taking harsh decisions to deal with any political disturbance carried out in the name of nationality or religion"

Approximately 1.2 million Tibetans died during the thirty years following the Chinese occupation in 1949. About 125,000 Tibetans followed the Dalai Lama into exile, to settle in India or other parts of the world. Due to population transfers of Chinese to Tibet and forced birth control of Tibetans still in Tibet, the Chinese in Tibet now outnumber native Tibetans. Almost all the monasteries in the country were systematically destroyed by the officially atheist Chinese Government and the practice of Tibetan religion (their primary way of life before the occupation) was strictly outlawed. It was especially forbidden to even possess a picture of the Dalai Lama. Policies to stamp out Tibetan culture are in effect even today. An official Chinese Government document from 1991 says: "We should oppose all those who work to split the motherland. There should be no hesitation in taking harsh decisions to deal with any political disturbance carried out in the name of nationality or religion"The Chinese are presently building a vast Tianamen style square complete with grandiose chandelier lamps at the foot of the Potala. Many Tibetan residences were demolished to make way for construction. The middle of the new square features a Chinese military aircraft. This is one small example of the erosion of Tibetan life and culture and the supremacy of Chinese culture and control. Tibetans are required to register their area of residence and travel outside this area is highly restricted. Tibetans have a very minimal participation in the Chinese controlled government administration. Tibetans are given last preference in the labor market and mostly scrape by selling or trading goods in the open marketplaces. Today, between 70 and 90 percent of small businesses in Lhasa, the traditional capital of Tibet are Chinese owned.

| There are more than a thousand different trees in the primeval forests of Tibet, of which the most common are firs, Yunnan pines, Tibetan Cypress, and dragon spruces. Half of Tibet's forests have been felled since 1959 providing the Chinese with $50 billion worth of lumber. The most common form of timber harvesting is clear cutting which has led to vast hillsides being denuded. Four countries depend on the rivers of Tibet for their sustenance. Some of the major floods in these countries during the last decade have been attributed to deforestation related siltation of Tibet's rivers. More than a quarter of Tibet's mineral resources have been extracted since 1959. Tibet contains the largest uranium deposits in the world. Uranium has been processed in Tibet leading to contamination of drinking water and the death of Tibetans in Ngapa, Amdo. Radioactive contamination of other groundwater is a great concern. China is reported to have stationed approximately 90 nuclear warheads in Tibet. WWW.Tibet.com, Select White Papers WWW.OneWorld.Org, Search: Tibet |  |

Before the Chinese invasion, every explorer in Tibet reported seeing vast herds of wildlife. "One great zoological garden!" said Joseph Rock in 1930. "Wherever I looked, I saw wild animals grazing contentedly." The animals had almost no fear of humans. Only in the wildest nomadic areas, where no crops were grown, did native Tibetans hunt wild animals.

Since the Chinese occupation, the herds have all but disappeared because of the folly of wholly unregulated shooting by soldiers and the loss of habitat that occurred as the simple subsistence lifestyle of old Tibet was squashed to fit Marxist ideals. As communes were required to raise livestock products for export to China, sensitive winter range in the most temperate valleys became radically overgrazed.

Today Tibet's wild animals are rarely seen except in such remote areas as the northern plains of the Changtang, the arid valleys of western Tibet, and the alpine grasslands of uninhabited parts of Amdo and Kham. With Tibet's low population and tremendous open space, there is a great potential for species to recover if the old environmental ethic of Tibetan Buddhism is reestablished.

From: The Dalai Lama - My Tibet, by Galen Rowell

Hope for the Future

|

Special Message from the Dalai Lama

"Our planet is our house, and we must keep it in order and take care of it if we are genuinely concerned about happiness for ourselves, our children, our friends, and other sentient beings who share this great house with us. If we think of the planet as our mother - Mother Earth - we automatically feel concern for our environment.

In my five point peace plan I have proposed that all of Tibet become a sanctuary, a zone of peace. Tibet was that once, but with no official designation. Peace means harmony: harmony between people, between people and animals, between sentient beings and the environment. Visitors from all over the world could come to Tibet to experience peace and harmony. Instead of building big hotels with many stories and many rooms, we could make small buildings, more like private homes, that would be in better harmony with nature."

From: The Dalai Lama - My Tibet, by Galen Rowell

Dalai Lama's Five-Point Peace Plan (presented 1987)

1. Transformation of the whole of Tibet into a zone of peace. Withdrawal of Chinese troups and military installations.

2. Abandonment of China's population transfer policy which threatens the very existence of Tibetans as a people

3. Respect for the Tibetan people's fundamental human rights and democratic freedom.

4. Restoration and protection of Tibet's natural environment and abandonment of China's use of Tibet for the production of nuclear weapons and dumping of nuclear waste.

5. Commencement of earnest negotiations on the future status of Tibet and of relations with the Tibetan and Chinese people

Postscript:

From a Traveler to Tibet's Mount Kailas, The Unique and Sacred "Center of the Earth",

The Crown Jewel of Tibetan Sacred Wonders

"Only he who has contemplated the divine in its most awe inspiring form, who has dared to look into the unveiled face of truth without being overwhelmed or frightened - only such a person will be able to bear the powerful silence and solitude of Kailas and its sacred lakes, and endure the dangers and hardships which are the price one has to pay for being admitted to the divine presence on the most sacred spot on earth. Those who have given up comfort and security and the care for their own lives are rewarded by in indescribable feeling of bliss, of supreme happiness. Their mental faculties seem to be heightened, their awareness and spiritual sensitivity infinitely increased, their consciousness reaching out into a new dimension - their individual consciousness giving place to an all-embracing cosmic consciousness." From: The Way of the White Clouds, A Buddhist Pilgrim in Tibet, by Lama Anagarika Govinda |

|